Fritz Stuckenberg

(Munich 1881 – 1944 Füssen)

Blooming Cactus

Watercolor on paper

15 3/8 x 18 3/8 inches

Signed and dated ‘stu VIII 29’ (top centre)

Provenance:

Private collection, Germany

Fritz Stuckenberg’s work reflects some of the most significant chapters in the history of German painting in the first half of the twentieth century, from expressionism to constructivism. Born in Munich in 1881, aged twelve he moved with his family to Delmenhorst, an industrial centre in Lower Saxony where his father held a managerial role in a large linoleum factory.

Stuckenberg attended school in Delmenhorst, nearby Bremen and Oldenburg, and after graduation was apprenticed as a theatre set designer in Leipzig (1901-1903). He subsequently studied painting in Weimar (1903-1905) and in Munich (1905-1907), and in 1907 he moved to Paris, the central experience of his formative years. Like many fellow artists, he frequented the Café du Dôme in Montparnasse, where regulars included Pablo Picasso, Amedeo Modigliani, Piet Mondrian, and Max Ernst, and travelled to the South of France. Stuckenberg admired the Fauvists’ palette of primary colours, and developed an artistic vocabulary that tended towards abstraction, influenced by Robert Delaunay. Quickly gaining a degree of recognition within avant-garde circles, he exhibited in many galleries in Paris, and only moved back to Germany in 1912.

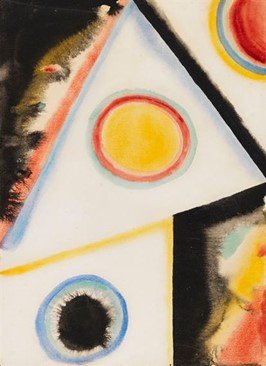

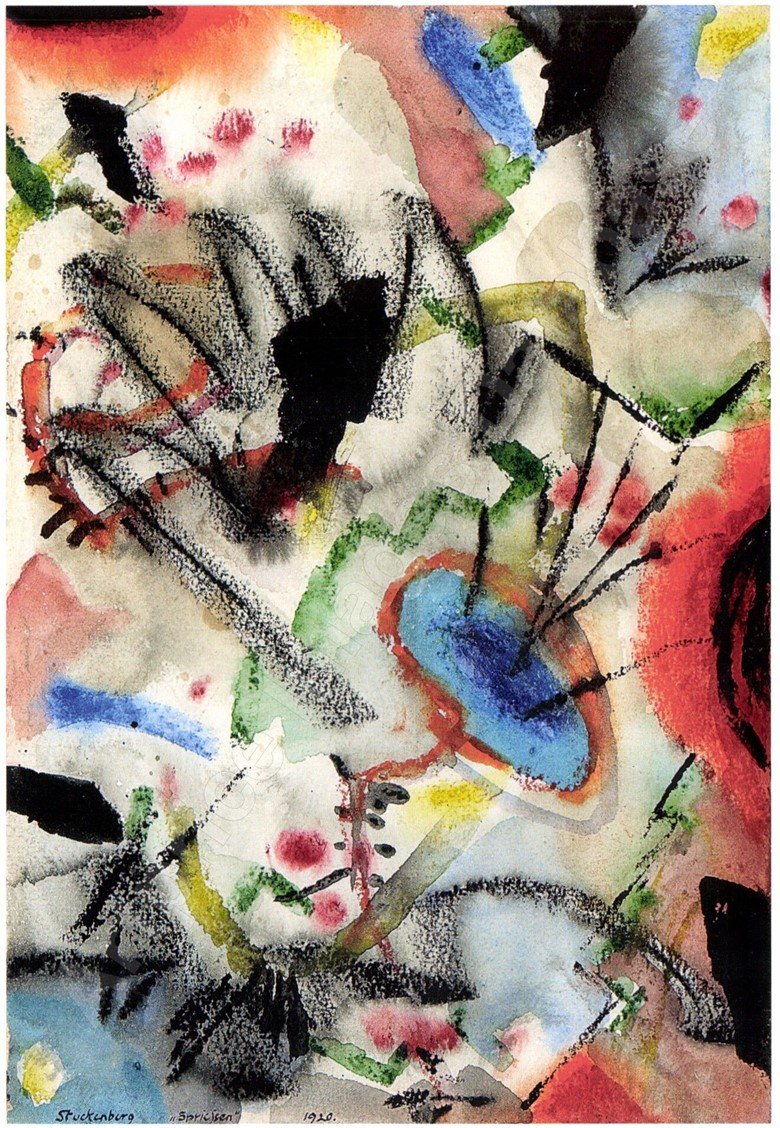

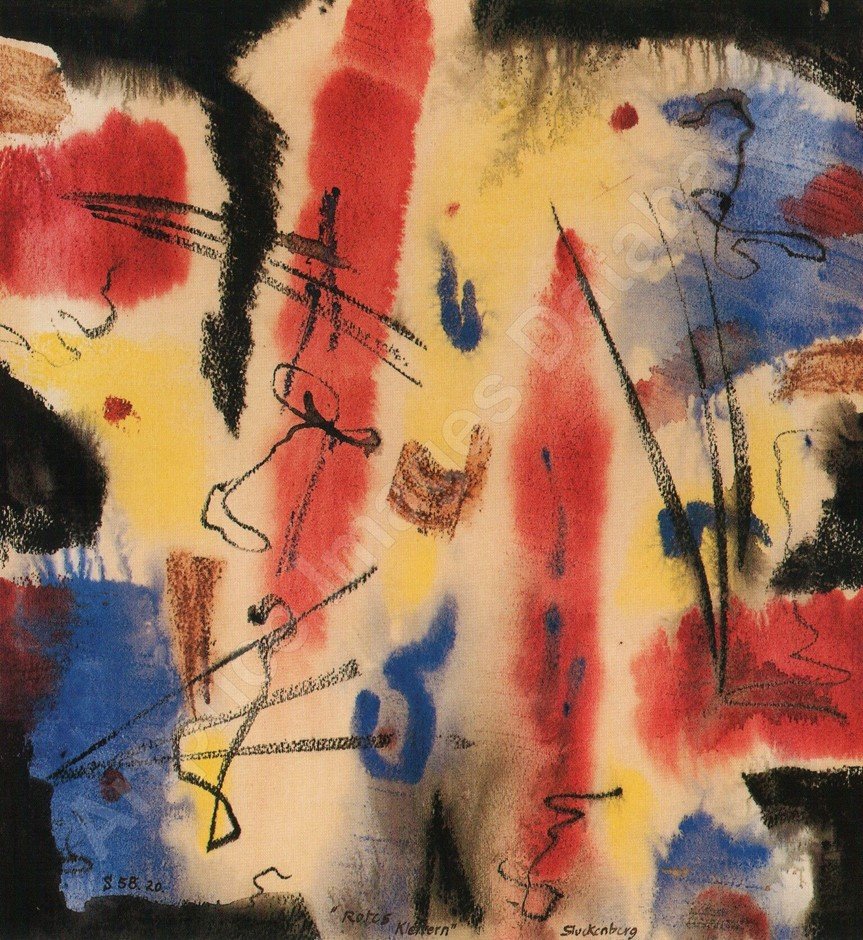

Now living in Berlin, the heart of German avant-garde ferment, Stuckenberg formed part of the group of artists associated with Herwarth Walden, himself an artist and the founder of magazine Der Strum (‘The Storm’). Stuckenberg’s work often featured on the publication’s cover, and in the exhibitions that Walden organised at the eponymous gallery, active between 1912 and 1932. Walden was instrumental in championing groups such as Die Brucke (1905-13) and Der Blaue Reiter (1911-14), and is generally considered one of the driving forces behind German expressionism. Compared to these currents in German art, Stuckenberg’s work tended towards a higher degree of abstraction, compounded – at times – by a markedly cubist style of fragmentation, as exemplified by his canvas The Lovers from 1919/20 (fig. 1; Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte, Oldenburg). Other paintings by Stuckenberg from the period immediately following the end of WW1 echo the abstract shapes and black lines of Wassily Kandinsky and the vivid palette of Franz Marc, as visible in Ohne Titel (Komposition mit großem Dreieck) from 1918 (fig. 2, private collection), Sprießen from 1920 (fig. 3; private collection), and Rotes Klettern from circa 1920 (fig. 4; private collection). A self-portrait (fig. 5) painted in 1915 in Berlin – where Stuckenberg met his future wife Margot, an artist within Walden’s circle – shows a young man of somewhat gaunt appearance, with a preternaturally concerned expression tinged with ambition.

In 1919, Stuckenberg left Der Strum and joined the socialist November Group and the Arbeitsrat für Kunst (‘Workers Council for Art’), an association of artists, architects and writers created on the blueprint of industrial workers councils and advocating broader public accessibility to avant-garde art. An artist of polyhedric output, Stuckenberg exhibited alongside Dadaist painters and members of the Bauhaus school, becoming an integral part of the discourse on German post-war avant-gardes.

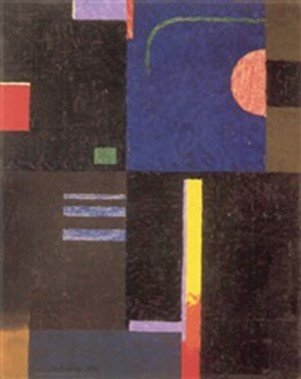

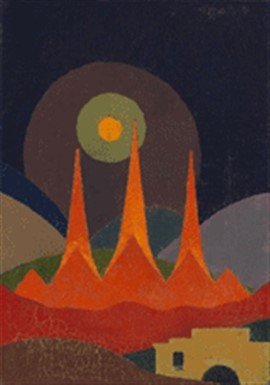

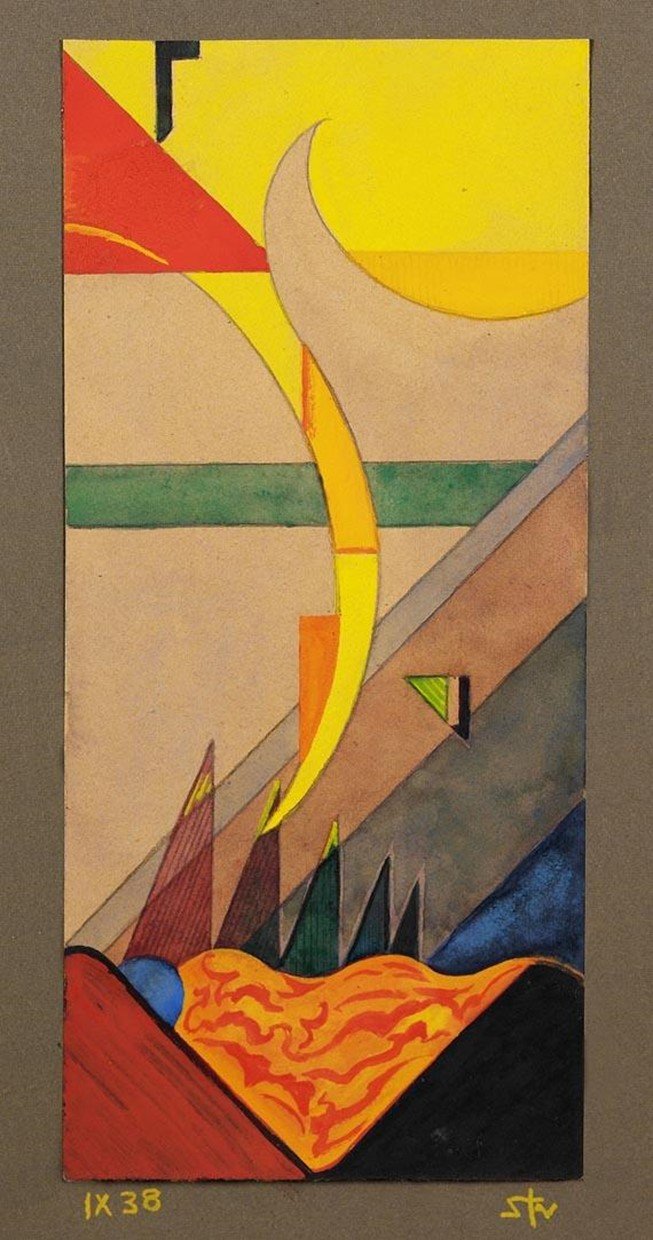

This phase of Stuckenberg’s career came to a halt in 1921, when financial difficulties and health problems forced the artist to move back to his parents’ home in Delmenhorst, where his work gradually took on a more constructivist quality and also embraced a fully figurative vocabulary, mostly in the form of floral still-lives. From the mid-1920s onwards, Stuckenberg’s language of abstraction adopted the austere formal quality of constructivism, with large, simple geometrical shapes interlocked on canvas (Mechanik, 1926; fig. 6, private collection). Progressively, his abstract compositions featured recognisable figurative elements, from the mountain landscape portrayed in Rotes Ragen (c. 1927; fig. 7, private collection) to the trees and valley in Abstract Composition from 1938 (fig. 8, private collection).

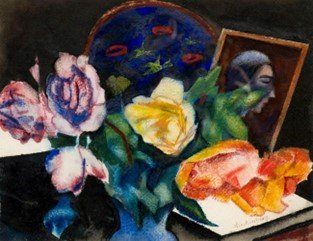

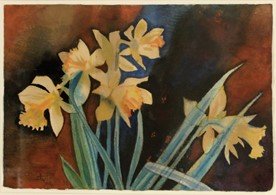

In parallel, from about 1920 Stuckenberg produced a series of canvases dedicated to flowers and plants, subjects charged with strong spiritual significance. Dogged by ill health and concerned by the social and political situation during the Weimar Republic, Stuckenberg saw in plants symbols of regeneration and endurance Blooming Cactus, executed in 1929, is characteristic of this chapter in Stuckenberg’s career, as he employed the technique of watercolour - one he had long favoured - to portray the delicate surface and colouring of the pink flower and the fleshy texture of the cactus leaves. Comparable works from this period include Daffodils from 1933 (fig. 9) and the undated Tulips in a Vase (fig. 10), where the painter rested on the fine, undulating stems of the flowers and effects of light on their petals. Highly personal, these floral watercolours do not align with any of the artistic movements Stuckenberg had joined or witnessed in Paris or Berlin, and arguably form the most original section of his corpus.

In 1937, Stuckenberg suffered a further setback, as his works in German public collections (Breslau, Chemnitz, Erfurt, Oldenburg, Weimar and Wiesbaden) were deemed “degenerate” by the Nazis and systematically destroyed. In 1941, affected by lung disease, he moved to the Bavarian town of Füssen, where he died three years later. In 1959, his widow bequeathed The Lovers to the Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte in Oldenburg, the first museum to host a retrospective exhibition of Stuckenberg’s work in 1961.